After investigating every aspect of the Curtis Flowers case, we were nearly ready to present what we'd found to District Attorney Doug Evans. But first we tried to learn all we could about him: his childhood, his years as a police officer and his record as district attorney. Then, finally, we met the man who's spent more than two decades trying to have Flowers executed.

June 12, 2018

We know that race was an important factor in the Curtis Flowers case. Flowers has been tried six times for the 1996 murders of four people at the Tardy Furniture store in Winona, Mississippi. He was first convicted by an all-white jury in 1997, and he was convicted three more times, always by nearly all-white juries. Flowers' case wasn't an aberration.

Over a 26-year period — from 1992 through 2017 — prosecutors excluded black prospective jurors at a much higher rate than whites, an analysis of jury selection data shows. Using information on more than 6,700 jurors in 225 trials during Doug Evans' tenure as the top prosecutor in Mississippi's Fifth Circuit Court District, APM Reports found that his office struck black people from a jury at almost 4 1/2 times the rate it struck white people. The prosecution struck 50 percent of eligible black jurors compared to only 11 percent of eligible whites. APM Reports also found that even when controlling for other, race-neutral factors raised during juror questioning, black jurors were still far more likely to be struck than white jurors who answered in the same way.

During jury selection, the juror pool is first narrowed by strikes for cause, meaning that the judge and lawyers strike jurors because their answers to questions indicate they can't judge the case fairly. Prosecutors and defense attorneys then go down the list of remaining prospective jurors in order and eliminate the ones they don't want on the jury with "peremptory strikes."

The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled it unconstitutional to exclude people from a jury based on race or gender. But that standard is difficult to enforce. Moreover, no agency tracks jury composition and selection in courtrooms across the country, at either the local or national level.

Though the APM Reports analysis offers just a snapshot of jury selection in one section of one state, it's still one of the most comprehensive investigations of race in jury selection ever performed in the United States.

We attempted to gather the race of jurors in all 418 trials that Doug Evans has prosecuted since 1992. It was available for 225 trials. Explore the data and how we compiled it.

The data we gathered showed that prosecutors in seven central Mississippi counties were far more likely to strike black prospective jurors than whites during jury selection. But the data alone didn't explain why that was happening. Was race really the determining factor? To find out, we crunched the data to account for other possible explanations for people being struck from a jury. We found that, all things being equal, race was one of the most powerful predictors of who would be chosen for a jury. The video below explains how we performed our analysis and what it showed.

In our analysis, we grouped together jurors who answered key questions in jury selection — such as did they have a family member with a criminal history or did they know the defendant — the same way. When we sorted jurors by their answers to these questions, we saw that black jurors were still more likely to be removed.

Percentage of potential jurors struck

Overall, the analysis showed that the odds of black jurors being struck were six times higher than the odds of a white juror being struck.

In the summer of 1966, John Rundle High School, where Doug Evans was an incoming freshman, was integrated by court order. Armed state troopers stood guard as African-Americans arrived to attend the formerly all-white school.

The town of Grenada was riven by violence and unrest that lasted for months. Mobs of angry white men beat young black students with axe handles as they headed to the nearby elementary school, which was also desegregating. Activists who demonstrated at the town square were pelted with rocks and bottles.

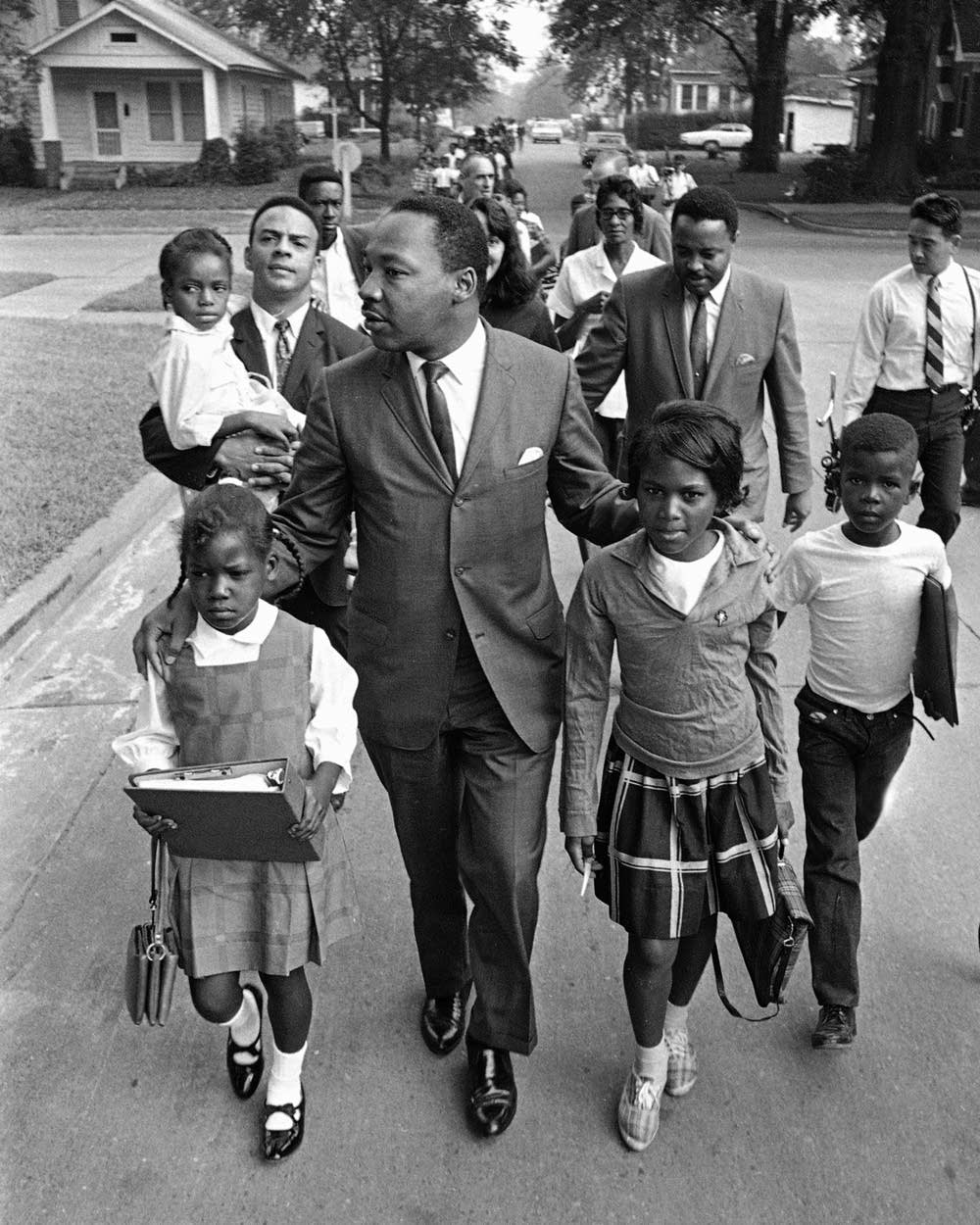

Civil rights leaders like Joan Baez and Martin Luther King Jr. marched through Grenada and accompanied several students on their treacherous walk to school. One of them was 7-year-old Eva Lemon.

The clashes continued into the fall. Law enforcement cracked down on peaceful black protesters, even arresting children. Little Eva Lemon was booked into the local jail in November.

So was her older sister, Estella Cox Williamson, who was 13 at the time. "They teargassed us after we got in jail, inside of the cell, and it was in the summertime. I can remember, me being that age, I was scared to death," Williamson recalls.

The sisters were part of the Grenada Freedom Movement, which led the protests in 1966. Organizers gathered at Belle Flower Church, in the heart of the black neighborhood, to listen to speeches and lead marches to the town square. Today, the landmark church still stands, but it's fallen into disrepair.

-DIANNA FREELON FOSTER, THEN A 15-YEAR-OLD STUDENT AT JOHN RUNDLE HIGH SCHOOL

When Doug Evans first ran to be the chief prosecutor of Mississippi's Fifth Circuit Court District in 1991, he was 38 years old. He'd grown up in the district and graduated high school there. He had studied criminal justice at a college just an hour away. In campaign ads, he showcased his decade in law enforcement, and his wife and two teenage kids.

The local bar association endorsed him as a "fine Christian man with unquestioned integrity." In his seven years as a lawyer, he'd worked in private practice, served as a judge in a misdemeanor court and been an assistant district attorney.

In 1991, he campaigned against his former boss, incumbent Ed Snyder. The men both ran as Democrats. It's a novelty of Mississippi politics that, even today, conservative candidates still run in local elections as Democrats, the party of the Old South.

Fulfilling another political tradition of the Old South, both Evans and Snyder stumped at the Black Hawk Political Rally, a gathering sponsored by the Council of Conservative Citizens, a white nationalist organization that's been designated a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center. The rally was a fundraiser for the Black Hawk Bus Association, which shuttled white kids from rural Carroll County to a private academy founded the same year the local public school was integrated by court order.

Evans ran on a tough-on-crime message. He promised to work tirelessly to indict and convict criminals. He said local youth needed to understand the dangers of drugs and that victims of crime should be treated with compassion. In campaign ads, he branded himself as "fair but firm."

Snyder was politically vulnerable. He'd crossed some of his constituents by prosecuting a well-connected woman for her husband's murder which, years earlier, had been ruled a suicide. Snyder's father, a state commissioner, had also recently been convicted on federal extortion charges and sent to prison.

In a hard-fought Democratic primary, Evans just edged out Snyder. The race was only decided after a recount. But Evans had an easy path to victory in the general election, where he faced no Republican opponent. And for the next 12 years, he held the DA's office uncontested.

In 2003, an attorney named Taylor Tucker, from the other side of the judicial district, finally challenged Evans. Tucker ran as a Republican on an anti-establishment platform.

"There's a system that's gone on for years and years and it's based on friendship, authority and money and cannot get out of that mold," Tucker said recently. "Those people have controlled for so many years that they're just not wanting to give up control. I was born and raised here. I felt that there was a possibility that we could change the system from within."

Tucker didn't even win his home county. Doug Evans took the seven-county district with 68 percent of the vote. He has never faced another challenger.

This isn't out of the ordinary. In a 2009 study, Wake Forest University law professor Ronald Wright collected data on prosecutorial elections in 10 states. He found that 85 percent of incumbent candidates ran unopposed. There are strong disincentives to would-be challengers. It's hard to unseat an incumbent DA (they win 69 percent of the races in which they have an opponent, according to Wright's data) and there's professional risk in trying to take down a powerful attorney in one's own community.

Wright's conclusion about prosecutorial elections? "They don't work. They just aren't very good methods of accountability," he said.

Most prosecutors around the world are appointed. America is the only country that elects them. Mississippi was the very first state to start doing so, in 1832, and all but four states followed. The idea was to end patronage postings and make prosecutors more responsive to local citizens.

"What we care about with elections is that you've got to go out there and explain to people what your platform is and what your policies have been and why they're good for us," Wright said. But in practice, this doesn't happen. "They never have to run. They're on the ballot, but they never have to go out and tell their story."

Short of listening to a stump speech, it's difficult for voters to appraise the performance of their district attorneys. Criminal prosecutions leave an enormous paper trail, but the records are difficult to access, even harder to parse and costly to obtain.

In an analysis of local news stories run in the year leading up to prosecutorial elections, Wright found that "whatever case was on the local television news or in the local newspaper, win or lose, that's the case that people were talking about during campaign events. ... Nothing about the big policies." This might help explain why Doug Evans has fought so hard to win a conviction in the Curtis Flowers case.

An elected district attorney cannot be fired. He is accountable only to the voters of his district, though they have little recourse if his name is the only one on the ballot. If Evans runs again and wins, he could hold office for more than 30 years. He is up for re-election in November 2019.

Natalie Jablonski

Rehman Tungekar

Parker Yesko

Will Craft

Dave Mann

Andy Kruse

Catherine Winter

Chris Worthington

Gary Meister

Johnny Vince Evans

Corey Schreppel