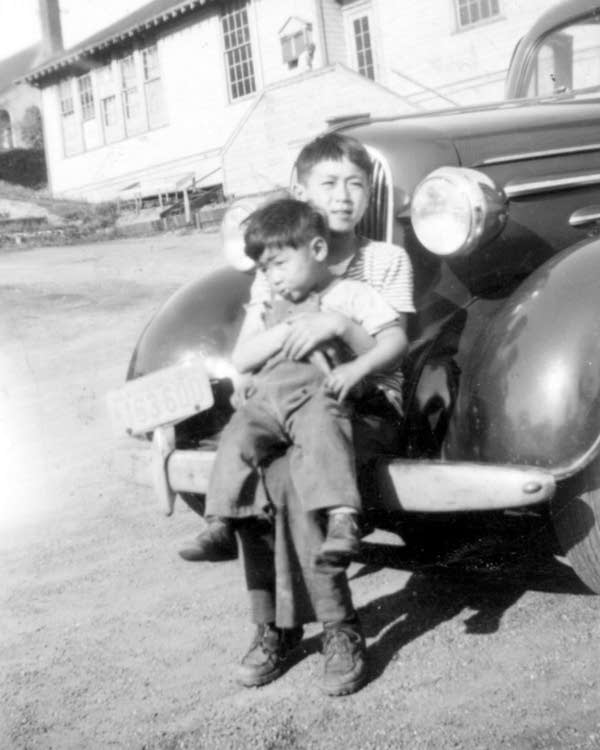

Chapter 7: Leaving Camp

At the end of 1944, the U.S. government lifted the order barring people of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast. Many people freed from camp faced racism and poverty as they tried to rebuild their lives. Some found that leaving camp was even harder than being sent there.

Roughly 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry were imprisoned in camps at the start of World War II. But almost from the beginning, some were allowed to leave. Many college-age students were sent east, to schools outside the West Coast exclusion zones. Farm laborers were recruited from the camps to harvest crops. In 1943, even more prisoners were allowed out. These were people the government decided it could trust, based on a loyalty questionnaire.

Some Japanese Americans leapt at the chance to leave camp for points east. Others waited until they were allowed to move back to the West Coast. That wouldn't be until 1945. But wherever they went, resettling after camp was hard — sometimes even harder than being sent there.

When Japanese American families moved out of incarceration camps, it was common for one or two members to leave ahead of the rest. Once they were established, they'd send for the others. The War Relocation Authority, which ran the 10 incarceration camps, set up offices across the country to help Japanese Americans resettle once they were freed. The WRA helped them find jobs and places to live, but it could do nothing to protect Japanese Americans from the racism they encountered outside camp. Some were terrorized by white people, especially in rural areas.

Most families had no idea what awaited them when they went home. When they were sent to the camps, they had been forced to sell their farms, businesses and belongings for a fraction of their worth. People also made arrangements to store what they could — in the closet of an apartment, in a friend's garage, in a church basement. Many Japanese Americans came home to find that those belongings were gone, their property destroyed.

Many people also had no place to live. They had been renters when they were forced into camp, and there was a severe housing shortage when they returned. Shelters were established up and down the West Coast where families could stay temporarily. But there are stories of people living in chicken coops, Judo schools and old farm sheds.

For most Japanese Americans incarcerated during the war, recovering from the experience would be a long, slow process. After camp, many didn't talk about it. They chose to put it behind them. But years later, a movement started to build. Japanese Americans began to demand that the United States government apologize for the incarceration and pay reparations.