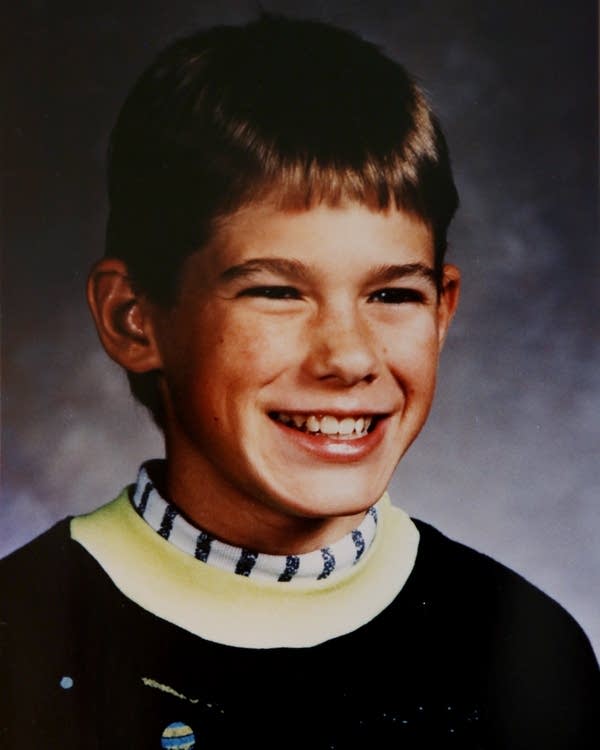

Joseph Ture Jr.

Just days after the shotgun killings of Alice Huling and three of her children, he was interviewed by Stearns County sheriff's deputies and then let go.

In the early morning of Dec. 15, 1978, Alice Huling and three of her four children were shot to death in their beds at their rural home near Clearwater, Minn. Only 11-year-old Billy Huling survived when he played dead under his covers as two shotgun blasts narrowly missed him.

The murders remained a mystery for decades. Several potential suspects were considered, including a Stearns County deputy who lived nearby and has since died. It wasn't until 2000 that a jury convicted a drifter named Joe Ture, largely based on a confession he allegedly dictated to a fellow prisoner, something he denied doing.

"I did not do any of these murders," said Ture, who claims to have been framed in order to close the cold case shootings.

Investigators had Ture in their grips just four days after the Huling murders. He was driving a car that had been reported stolen and was harassing waitresses at the Clearwater Travel Plaza near Interstate 94. One of them called the police. "I'm in there having breakfast, and I'm trying to get a couple dates with a couple of the waitresses," Ture said in a prison interview with APM Reports. "That's how I get most of my dates is with waitresses."

The police searched the car and found a metal rod wrapped in a steering wheel cover, a small toy car and a ski mask. Experts matched the rod to a bruise on Alice Huling's body. Billy Huling later described the toy car as similar to one of his that had gone missing. The items were turned over to Stearns County Sheriff's Deputy James Kostreba, who had been one of the first to arrive at the Huling crime scene. He and another detective interviewed Ture and, after evading several questions, he was released.

Ture would go on to conduct a string of rapes and murders for which he was later convicted. He is serving multiple life sentences at Stillwater state prison.

Born in February 1951, Ture spent most of his early life in and around St. Paul. His parents divorced when he was 10, and he said he wound up in an orphanage and a reformatory. He didn't get along with his father's new wife, he said, and his mother was deemed unable to look after him. "My ma, she was just moving around here and there," Ture said. "So she wasn't a fit mother to live with, they said."

When Ture was 18 or 19, he said, he joined the U.S. Marine Corps but made it through only six months. He returned to the St. Paul area, rarely holding a job for long. He worked at the Ford plant in St. Paul, at junk yards and at car dealerships as a mechanic or "lot man." Sometimes he lived in his car. Often he was characterized as itinerant.

Ture, who as a young man wore shoulder-length blond hair and bushy sideburns, talks a lot and views himself as a truth teller. "I call a spade a spade," he said. "I had a lot of problems with some women because I tell them where it's at. If I don't like someone, I don't beat around the bush."

In 1981, more than two years after the Huling murders, he was convicted of abducting and raping an 18-year-old woman and a 13-year-old girl in separate incidents near Lake Street in Minneapolis. He was also convicted of attempting to kidnap and rape a 20-year-old woman, who escaped by burning his face with a cigarette.

After that, Ture was convicted of the 1980 abduction, rape, and murder of 19-year-old Diane Edwards. Edwards, the subject of the Husker Du song "Diane," was walking home from her waitressing job at a Perkins restaurant in West St. Paul when she was forced into a car. Her naked body was found face down in a ditch nearly two weeks later, her clothing piled beside her. Ture confessed to the murder but now says he was just "playing games" with authorities and is innocent.

In 1998, he was convicted of bludgeoning to death 18-year-old Marlys Wohlenhaus in her family home in Afton, Minn., in 1979, based partly on the same dictated confession used in the Huling prosecution.

"I did a lot of bad things," Ture said. "I stole from this and stole from that. I stole cars. Shit like that, but I never hurt a body. I never hurt a certain person. If I burglarized something, it was a business and there was nobody there, hopefully."

Retired Stearns County Detective Lou Leland provided a different portrayal. "I spent hours and hours and hours with him," Leland said. "He is a very mixed-up character. He had a bad bringing-up. Life was not easy for him. I don't feel sorry for him. But I can see why he kind of didn't like women. And he did probably more than what we got him for."

Of the Huling murders, Leland said, "He did the deed."

In 2001, the Minnesota Supreme Court upheld Ture's conviction for the Huling murders, and in 2004 upheld his conviction for the Wohlenhaus murder.

More profiles

ABDUCTED BOY

Jacob Wetterling

KILLER

Danny Heinrich