Lawsuit saves massive reading experiment

The Trump administration tried to kill the largest reading experiment ever funded by the U.S. Department of Education’s research arm — just months before the yearslong study was complete. The administration agreed to finish the research only after it was sued.

The Zoom call was supposed to be a regular check-in for the team at Boston University. They’d wrapped up work on a massive, federally funded study of a system to detect when kids are having trouble learning to read and get them help immediately. The team was just waiting for the data on the early warning system to be analyzed.

But one of the professors, Nancy Nelson, interrupted the call. She had just gotten an email: The Trump administration was canceling the study — the largest experiment on reading ever funded by the Institute of Education Sciences, the U.S. Department of Education’s research arm.

The study had been 6 1/2 years in the making, and results were scheduled to be released in a matter of months. Ninety-three percent of the funds had already been spent. But the Trump Administration was saying the $41 million project was over. Three years of data, collected from more than 100 elementary schools in seven states, was being shelved.

Carol Dissen, a teacher trainer on the Boston University team, was stunned. She never expected it, “never in a million years.” She thought about all the students she believes would have benefited from the early warning system, and the tears flowed.

Disadvantaged kids “rely on our school system in order to change the trajectory of their lives,” Dissen said, still choking up as she recalled the February meeting months later. “We worked hard for three years to show that it works and that you can make a change for those students. And to hear that the data wasn’t going to be analyzed and shared, it’s devastating — absolutely devastating.”

If it hadn’t been for legal action, the results of the study on the early warning system might never have been released. But in response to a lawsuit filed by two research associations, lawyers for the Trump administration said in June that it would voluntarily reinstate the contract for the study — a concession it argued should allow the administration to go forward with its other deep cuts to education research.

That study was just one of about 106 education-related contracts totaling $820 million that the Department of Government Efficiency terminated. The abrupt cancellation meant researchers missed their year-end data collection, punctuating large-scale experiments and longitudinal studies with question marks. They cut students off from services, taking mentors away from high school students with disabilities trying to plan for life after graduation.

A spokesperson for the Department of Education did not respond to an email requesting comment.

Tabbye Chavous, executive director of the American Educational Research Association, one of the groups that filed suit, said that the administration did “begin to backtrack” by restoring some contracts. But she said that most of the institute’s research and data functions have not been restarted, in spite of Congressional mandates, and the layoffs have left it without the staff necessary to complete that work.

When contractors resume the early warning system study, they will be reporting to a much-diminished agency. Layoffs have shrunk the Institute of Education Sciences to a tenth of its former size. The specialist who oversaw the contract is gone. And researchers worry about how the cancellations will affect future studies — and schools’ willingness to use that research in their decision-making.

It’s an episode that highlights the new administration’s approach to governing — flipping projects off and on, seemingly with little regard for the consequences, all in the name of efficiency.

“What’s efficient about that?” asked Kim Gibbons, a researcher at the University of Minnesota who was also involved in the study. “It doesn’t make any sense to me. But probably, like all of us, I’m learning a lot of things don’t make sense right now.”

How the early warning system works

The early warning system at the center of the reinstated study is formally known as a multi-tiered system of support for reading. The idea is to identify struggling readers early and get them targeted help before they fail.

The system is modeled after medicine — the same way doctors monitor symptoms and escalate treatments for a worsening illness. A person with a fever might take a day off work to rest. If it doesn’t go away, they’ll get a check-up from a doctor and maybe some medication. But if the bug lasts, they might need a stronger prescription.

The early warning system takes a similar approach, dosing up the intensity of instruction based on student needs. The system starts with a strong reading curriculum for all students, adds small-group lessons for those falling behind and provides one-on-one interventions for the most at-risk students. Testing continues throughout to measure how students respond.

Before, “you had to wait to fail in order to be eligible for special education,” said Nelson, the Boston University professor. “You had to be far enough behind your peers that you were found eligible.” The idea behind the early warning system, Nelson explained, “was to try and provide some support to students between general and special education. It really created that supplemental space that was missing before.”

A 2015 federal law recommended schools adopt this rapid response system. In the years after, many schools said they’d added it, but researchers agree that few implemented it well.

So in 2018, the Institute of Education Sciences hired contractors from the American Institutes for Research, a nonprofit organization that conducts social science research, to run the experiment.

Mike Garet, a vice president at the American Institutes for Research, said each component of the early warning system has lots of research to back it up, but the model hadn’t really been tested in an experiment. They had to see if the benefits of the system would be worth the teachers’ time.

“You could imagine a school that could spend a lot of time trying to schedule students’ assessments, scoring them, having meetings about them, scheduling (small-group) instruction and keeping track of the materials. And they spend so much time doing all that, actually they don’t have enough time left to teach reading,” Garet said.

“There’s a lot of theoretical arguments for why it should work,” he added. But until this study, “we didn’t really look carefully at all the engineering details that are required to do that well and to get good results.”

The federal government’s large-scale evaluations don’t just confirm whether a program works in theory: They’re meant to reveal what it takes to make it work in hundreds of classrooms with different students.

Over 6 1/2 years, right through the pandemic’s closures, the contractors from Garet’s organization identified two promising models of this early warning system, recruited seven school districts to join in a randomized experiment and collected three years of data. They methodically compared how the two models fared against the way schools usually operated — amid the messy reality of a large-scale rollout.

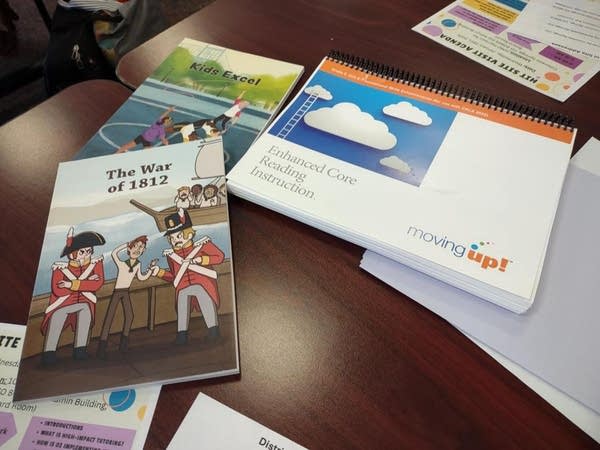

Annette Sisler, an elementary school principal in Junction City, Oregon, adopted one of the models, Enhanced Core Reading Instruction, this school year. Before her school adopted the model, Dissen, the education consultant from Boston University, had asked Sisler to follow a small group of children throughout the day, observing what lessons they received.

Sisler remembered one first grade girl who did well in a phonics lesson with all her classmates, smiling and engaged. But later in the day, with a different phonics lesson in a small group, she looked confused. Then, in yet another phonics lesson for her special-education class, she became so frustrated that she kicked another student. The instruction was disjointed, Sisler found.

“It was all out of line,” Sisler said. The student “doesn’t know what lesson she’s on, what she’s supposed to be learning, how to apply it. We weren’t priming her little brain to then be ready to read.”

Sisler said the new model brought lessons into alignment. After just one year, the share of her second grade students struggling with reading fluency dropped from 43% in the fall to just 8% in the spring.

School districts want to do what’s right for their students, Nelson, the Boston University professor, said. But they need studies to know what’s actually right for their students. “In the absence of those data, they’re doing it a little bit more blindly.”

Most research contracts remain frozen

The reinstatement of the early warning system study remains an exception. Of more than 100 canceled contracts from the Institute of Education Sciences, the Trump administration has reinstated only 12 of them, according to a June court filing and a review of federal spending data. Lawyers said the administration is reevaluating whether to reinstate or rebid up to 16 others.

By reinstating this one contract, the administration’s lawyers argued the department had fulfilled its congressionally mandated duty to evaluate how effectively students with disabilities are being taught. They argued they shouldn’t have to bring back two other large-scale special education studies. A longitudinal study that had been going on for 14 years and a $45 million experiment to help students with disabilities succeed after high school both remain dead, according to the administration’s lawyers.

Researchers say the cancellations are already affecting other federally funded studies, as school districts are now hesitant to sign up for experiments that could be nixed midway through. It already takes a lot of convincing to sign districts up for a randomized experiment. Only some of their schools will get the promising program that’s being studied, and evaluators will be a constant presence, monitoring compliance and collecting data. Nelson said the disruption of the early warning system study left some school superintendents “skittish” about participating in one of her follow-up studies.

Education researchers know that protecting their relationships with schools is one of their most important jobs, Nelson said. The Trump administration’s actions were “a major, terrible example of how to completely disrupt those relationships,” she said. She said the cancellation had only increased “mistrust” in research among educators.

While a few studies are running again, the Institute of Education Sciences now has limited capacity to undertake future large-scale experiments — and then translate the findings into practice.

“It’s a critical activity, finding out what works for whom under what circumstances,” said Russ Whitehurst, the institute’s founding director under President George W. Bush. “You can’t do it if you don’t have offices that are equipped to collect and disseminate the information.”

The Institute of Education Sciences, for instance, distilled takeaways from research in handy practice guides for teachers. Those contracts were canceled and aren’t coming back.

Garet, the American Institutes for Research vice president, said the early warning system study shows just how hard it is to get school systems to change. It takes far more than publishing a paper, even one that reports significant positive effects.

“Unfortunately,” he said, “scientific results aren’t self-implementing.”