Climate change has long been a threat that loomed in the future, the stuff of computer modeling and expert forecasts, an issue many policymakers treated as a theoretical calamity we wouldn’t confront for years to come. But no longer. Communities across the United States are experiencing the effects of climate change in the here and now. Floods, fires, mudslides and storms — fueled by a warming climate — are devastating homes, towns and lives.

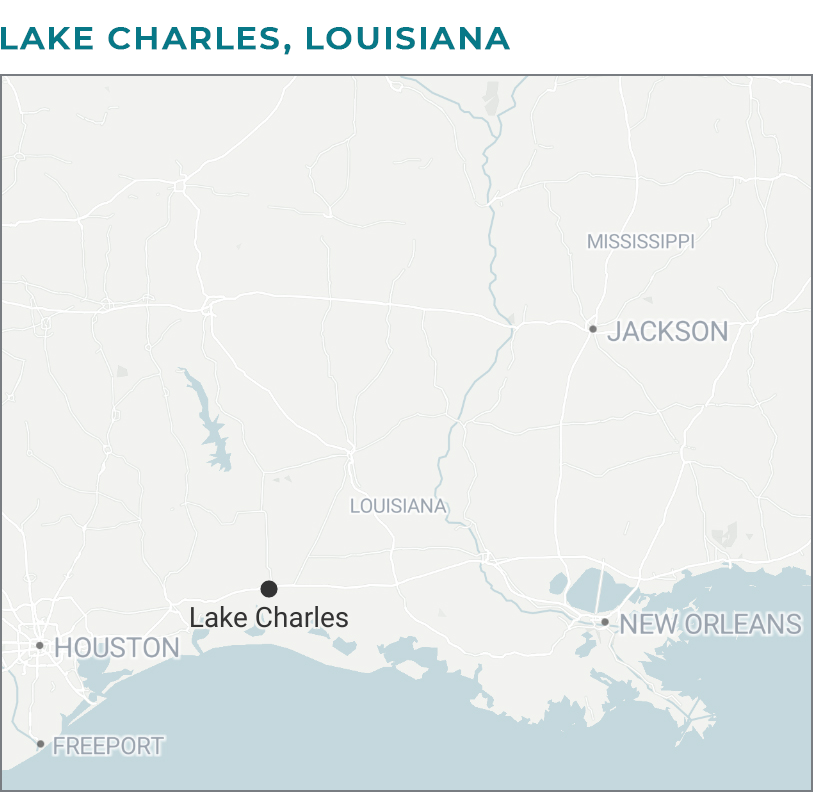

Perhaps no place has endured more than Lake Charles, Louisiana. The city of 85,000 people tucked about halfway between New Orleans and Houston was hit by four federally declared disasters in just nine months. Between August 2020 and May 2021, Lake Charles saw back-to-back hurricanes, a week-long ice storm and a historic flood.

Scientists say it’s impossible to attribute the string of storms entirely to human-caused climate change. But it is clear that climate change is contributing to a growing number of severe storms, which gather strength from warming seas. Gabriel Vecchi, a professor of geosciences and director of the High Meadows Environmental Institute at Princeton University, said what happened to Lake Charles offers important lessons.

“It doesn’t take a lot of imagination to understand that the challenges that we are seeing today,” Vecchi said, “are [often] the very types of events that we expect to become more intense and more frequent in the future.”

Tarps cover Christ The King Catholic Church in Lake Charles, Louisiana. (Photo by Ben Depp for APM)

Residents of Lake Charles barely had time to recover from one storm before another one hit. Adding to the problem was a painfully slow response from the federal government and insurance companies. City officials have pleaded with the federal government for help rebuilding, but what they’ve gotten so far is limited.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) denied more than two thirds of the applications it received for housing assistance in Lake Charles after the hurricanes alone, according to federal data. Many families whose houses were severely damaged have been left on their own to deal with repairs and find temporary places to live, sometimes for months, in the midst of a global pandemic that’s been catastrophic for southwest Louisiana.

Poor people in Lake Charles, a city that was already economically and racially segregated, have had a harder time. Poor people reported having trouble accessing aid from FEMA, and poorer areas of the city were slower to receive insurance payouts, if they received insurance money at all. The storms deepened the city’s existing inequalities.

“There are certain neighborhoods that you would drive through in Lake Charles and you would see homes that literally have not been touched,” Mayor Nic Hunter said in May. “We’re talking about money for underserved communities.”

Many towns have recently experienced such trauma. Every week seems to bring news of another 100-year storm or record-breaking heat wave, drought or forest fire. The United States saw 22 different weather-related disasters last year that caused at least a billion dollars of damage each. It was a new record. Vecchi and other experts say we need to prepare for a future where disasters pile up without time to recover, and federal agencies and aid groups can’t keep up. What the people of Lake Charles endured this past year shows us our future.

Aug. 27, 2020: Hurricane Laura

Hurricane Laura came ashore as a Category 4 storm, with winds of more than 150 miles an hour. It was the most powerful hurricane to hit Louisiana since the 1850s — stronger even than Hurricane Katrina. The storm surge reached 18 feet in some spots on the Louisiana coastline. The southwest corner of the state is a hub for petrochemical production and oil refining, and more than 30 potentially hazardous spills were reported in the days after the storm. In Lake Charles, the damage from Laura’s winds was catastrophic.

(Photo by Ben Depp for APM)

Dominique Darbonne, 32: musician and parent of two

When Dominique Darbonne returned home from evacuating with her family, she found much of her upper-middle class, predominantly white neighborhood had been seriously damaged, including the home she owned with her husband, a financial planner and guitarist. Darbonne had grown up in Lake Charles and was raising her two kids there, working part-time at her family’s chain of car washes and singing in a popular local band called Flamethrowers. (They bill themselves as Louisiana’s “No. 1 party rock cover band,” and they’re big at weddings.) Darbonne’s family resolved to stay and rebuild.

Oct. 9, 2020: Hurricane Delta

The 2020 hurricane season was busy. Scientists exhausted their alphabetical list of storm names by mid-September and resorted to using letters of the Greek alphabet for only the second time ever. A few weeks after Laura struck Lake Charles, another hurricane, this one named with the Greek letter Delta, began tracking toward the city in early October.

“You can’t draw any conclusions from one year, full stop. But the probability of having two storms in a row like that does go up in most of our simulations if you keep warming the climate,” said Kerry Emanuel, a climate scientist at MIT. “So the probability of something like that, we do think, is increasing and will continue to increase.”

Delta was less powerful than Laura, but the hurricane flooded neighborhoods in Lake Charles that were still cleaning up debris and tarping roofs. The back-to-back storms revealed structural damage at Dominique Darbonne’s home that wasn’t covered by insurance. The bill to repair it would exceed $80,000.

Half the housing stock in Lake Charles and the surrounding parish sustained damage from the hurricanes, according to an analysis by a national consulting firm.

Blue tarps still covered roofs in Lake Charles in July, more than 10 months after Hurricane Laura. (Photo by Ben Depp for APM)

Insurance inequities

Lake Charles had pre-existing, deep patterns of residential segregation, with disparities in median household income and poverty rates among white and Black residents. The storms threatened to make those inequalities worse. Insurance data obtained by American Public Media shows predominantly Black neighborhoods and low-income neighborhoods were left waiting for a greater share of their insurance money at the end of 2020. The charts below show how much money insurance companies had paid in areas of Lake Charles.

Whiter neighborhoods have gotten insurance payouts faster ...

... and so have wealthier neighborhoods

Payments were flowing faster to predominantly white neighborhoods and higher-income neighborhoods, and those parts of the city were visibly further along in their recovery as the months ticked by.

Households that didn’t have insurance to cover their losses could turn to FEMA for help. FEMA provides rental aid, money to replace damaged belongings, and even temporary housing to families whose homes suffered severe damage. But the rollout of FEMA’s programs in response to these hurricanes was bumpy.

In and around Lake Charles alone, the storms had destroyed or structurally damaged approximately 12,000 housing units. But FEMA provided temporary homes — RVs, campers, or apartments leased directly by the government — to just 2,400 households. At one point, FEMA officials said it would take a full year to finish moving families in.

Mosswood Estates, a gated trailer community leased by FEMA to house those displaced by hurricanes. Sulphur, Louisiana. (Photo by Ben Depp for APM)

(Photo by Ben Depp for APM)

Roishetta Sibley Ozane, 36: Community organizer and single parent of six

In January 2021, Roishetta Sibley Ozane drove through the city to survey housing damage for the nonprofit where she worked. “I was encountering several homeless people and several families who were sleeping in their cars, in their front yard,” Sibley Ozane said. “They didn't have anywhere to stay.”

Sibley Ozane had also struggled with housing in the wake of the hurricanes. A tree fell on her rental home, and her furniture and appliances were soaked. FEMA gave Sibley Ozane more than $6,100 to replace her belongings and find new housing for herself and her six children, according to documents reviewed by APM. Sibley Ozane racked up large hotel bills while her family was evacuated for the storms and briefly moved in with a friend afterward but couldn’t find a place to stay long-term. Rents had jumped, and Sibley Ozane said she’d been relying on a Section 8 voucher to help pay her way before the hurricanes.

As a last resort, Sibley Ozane moved her family back into their damaged house in Westlake, an industrial hub just outside Lake Charles. When she requested additional rental assistance from FEMA, Sibley Ozane claims the agency denied her because she had gone back to live in a damaged house. This is consistent with FEMA’s written policies. “I was so in shock that I didn’t even react, really,” Sibley Ozane said. “You’re going to punish us because we’re going back to our home? We can’t stay away from it forever.”

Feb. 11-19, 2021: A deep freeze grips the southern U.S.

In early February, the United States descended into a deep freeze. Arctic cold fronts swept across the Midwest and down to the Gulf Coast, the kind of rare weather event that climate experts say will become more frequent over time. Temperatures in Lake Charles dropped to their lowest point in decades, with slush and ice forecast for days.

Sibley Ozane started to worry about the families she’d met who were sleeping in tents, cars and RVs around Lake Charles. She began posting her personal information on Facebook, urging people to contact her if they needed a warm place to stay. “I really didn’t know how I was going to be able to do it,” Sibley Ozane said, “but I had that desire to make sure these people were safe and nobody froze to death.”

Dominique Darbonne, the musician whose home had been wrecked by the hurricanes, stumbled across Sibley Ozane’s posts as she looked for information about emergency housing options. The women can’t remember who reached out to whom first, but on Valentine’s Day they met in person and began paying for food and hotel rooms for people out of their own pockets.

Roishetta Sibley Ozane and Dominique Darbonne in February.

During the winter storm, Sibley Ozane and Darbonne said they provided temporary housing for more than 300 people. They solicited donations on Facebook to help cover costs, bringing in at least $30,000 in one week. The deep freeze was disastrous across much of the South, including Texas, where the electrical grid failed and more than 210 people died.

In Lake Charles, the winter storm was the third federally declared disaster in less than six months. After it passed, Darbonne and Sibley Ozane decided to continue providing mutual aid under the name Vessel Project. They organized food giveaways, household supply drops and continued booking hotel rooms for people who’d lost their homes to the storms.

(Photo by Ben Depp for APM)

JJ Jones, 55, and Alexis Sheridan, 36: Former renters and parents of two

Alexis Sheridan and her fiancé, JJ Jones, were one of the families Vessel Project paid to house throughout the winter and spring of 2021. Sheridan and Jones had moved into a tent after their rental home was damaged and, they claim, the landlord eventually pushed them out. According to Sheridan’s caseworker, FEMA gave the couple $1,600 for rental assistance. Sheridan found out she was pregnant over the winter.

When Sheridan requested extra help from FEMA in February 2021, records show her application was denied. The agency said it couldn’t provide assistance as long as Sheridan lived in “non-traditional housing.” In other words, because Sheridan and Jones were living in a tent, FEMA said it wouldn’t help them.

Sheridan and Jones were trapped in a chicken-and-egg dilemma with FEMA. The couple said they had a hard time finding an affordable rental or even a shelter that would accept families, since they weren’t comfortable splitting up during Sheridan’s pregnancy. “My biggest fear right now is, you know, my baby being born, and I have nowhere to go,” Sheridan said.

By spring, Vessel Project was out of money, but Darbonne and Sibley Ozane were still paying out of pocket when they could to house Sheridan and Jones in hotel rooms.

In early May, President Joe Biden traveled to Lake Charles to promote his infrastructure package. The city had an interstate bridge in need of replacement, but elected officials representing Lake Charles had been begging for additional aid to help the city recover.

In his remarks, standing on the Lake Charles waterfront — near the same picnic tables where Alexis Sheridan and JJ Jones had camped throughout the spring — the president pledged to help the city rebuild.

“I believe you need the help. We’re going to try to make sure you get it. But the people of Louisiana always pick themselves up, just like America always picks itself up,” Biden said.

He continued: “I promise you, we’re going to build back better than ever. More resilient. And build back in a way that all we build is better able to withstand storms that are becoming more severe and more frequent than ever.”

President Joe Biden speaks in Lake Charles with the Interstate 10 Calcasieu River Bridge behind him in May. (Photo by Alex Brandon | AP)

The president left town without taking questions from reporters. In the weeks afterward, Biden’s administration would announce a $4.5 billion investment in “climate resilience” projects to bolster basic services, infrastructure and housing in communities that are vulnerable to climate-related disasters.

Weeks went by without word of additional aid for Lake Charles or the other communities devastated by back-to-back storms. It would have to be approved by Congress, and a billion-dollar aid package is currently on hold in the Senate.

May 17, 2021: Deadly flash flooding

In May, nine months after Hurricane Laura, Lake Charles was still cleaning up. Debris still littered the streets, and partially clogged storm drains and bayous would contribute to the next disaster. The morning of May 17, a massive band of thunderstorms moved across the region.

Parents use boats to pick up students from schools in May after more than a foot of rain in Lake Charles. (Photo by Rick Hickman | American Press via AP)

Seemingly out of nowhere, more than a foot of rain fell on Lake Charles. Flash floods cornered people in their cars, including Roishetta Sibley Ozane, who was out running errands before her oldest child’s high school graduation. At least one person in Lake Charles died, trapped in a submerged vehicle. There were tornado warnings throughout the day and reports of funnel clouds touching down in outlying communities.

In the aftermath, Nic Hunter, the city’s Republican mayor, told The Guardian that climate change was clearly taking a toll on Lake Charles. “I know that phrase can engender a lot of emotions with different people,” Hunter said, “but it is real and it is happening.”

After the flood, Vessel Project got to work distributing cleaning supplies and delivering meals for families around Lake Charles. Sibley Ozane moved into a trailer supplied by FEMA with her six children. She hoped to buy a house but told APM she was expected to be out of the trailer within a few months. Dominique Darbonne’s family got a low-interest federal loan through the Small Business Administration to rehab their home. They moved back this summer.

But both Sibley Ozane and Darbonne felt uneasy about the future. The system for helping people through disasters hadn’t held up in Lake Charles. Another hurricane season began in June, and their city was still struggling to recover from the last one.

“Everything that could happen was happening,” Sibley Ozane said. “And we were just put on the back burner, and people forgot to go back to the pot on the back burner and take care of it. So we’re just kind of burning here.”

Contraband Bayou runs through Lake Charles and often overflows when there is severe rain. (Photo by Ben Depp for APM)

“In Deep: One City’s Year of Climate Chaos” is available in the APM Reports Documentaries podcast feed.

REPORTER

Lauren Rosenthal

HOST

Renata Sago

PRODUCTION TEAM

Annie Baxter

Jamie Hobbs

Chris Julin

Kristine Liao

Lauren Rosenthal

Kori Suzuki

DIGITAL EDITORS

Andy Kruse

Dave Mann

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Chris Worthington

FACT CHECKER

Eric Ringham

AUDIO MIX

Johnny Vince Evans

THEME MUSIC

Jelani Bauman

SPECIAL THANKS

Sasha Aslanian

Lauren Humpert

Samara Freemark

Catherine Winter